Mighty Drive

Utah's desert national parks are a roadtrip and outdoor adventure for all seasons.

An easy half-mile after the end of Scenic Drive, hikers in Capitol Reef National Park start seeing faint etchings on the slickrock canyon walls. Some marks look like nails punched into the stone to form crude, bold initials. Other scratches run in spidery, ghostly swirls, the handwriting of bygone times, spelling out names and dates: M Larson, NOV. 20, 1888.

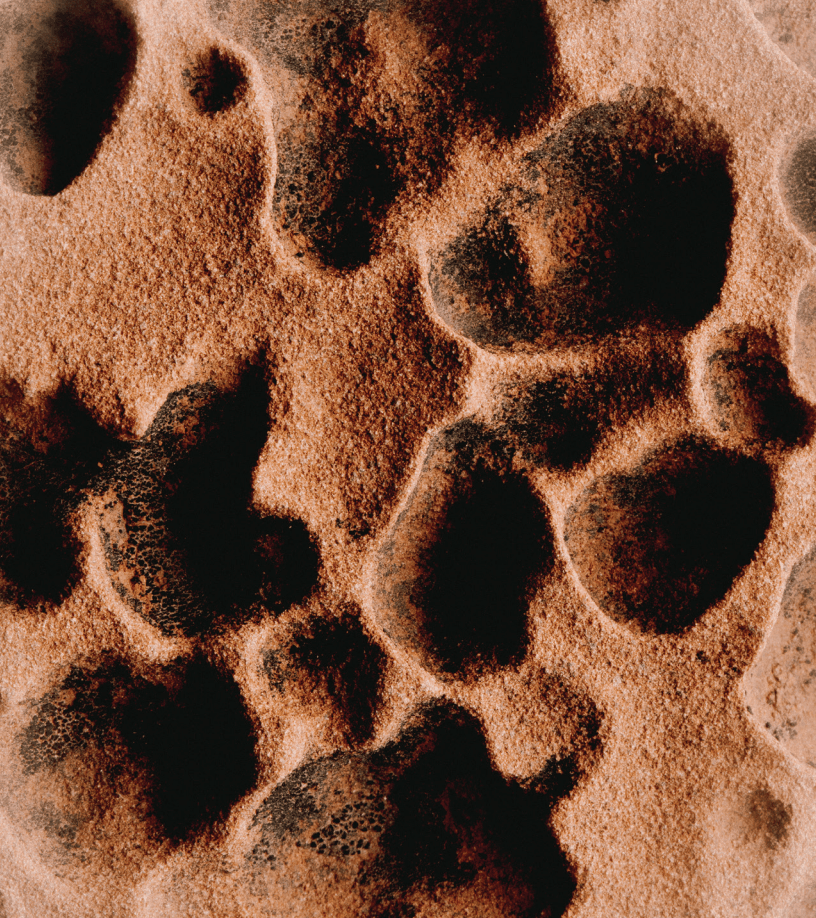

The inscriptions record the passage of prospectors, Army surveyors, archaeologists and, especially, farmers drawn to the Waterpocket Fold, a river-fed valley oasis in southern Utah’s stunning desert. Capitol Reef now holds the Fold and the wondrous geology that erupts all around the Fremont River. Scenic Drive’s eight-mile course cruises past layers of rust-red, green-gray and creamsicle-orange rock formations, every 100 yards demanding a stop and a stare. Other hikes climb up above this canyon country to soaring arches and sweeping views. But Capitol Reef’s human touches the Pioneer Register names, Native petroglyphs, old orchards, outlaw lore give this place texture and complexity that make it feel like a landscape you could explore endlessly.

And Capitol Reef is just one of the national parks strung across Utah’s southern reaches, part of the “Mighty Five” with Zion, Bryce Canyon, Canyonlands and Arches. (That’s from west to east, more or less.) This circuit draws millions of travelers across a wild, rainbow-hued ocean of public land that also includes Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Vermilion Cliffs National Monument, just beyond the Arizona line. Some Utah state parks would be national parks in any other country.

Versions of this odyssey can be done year-round. In winter and early spring, it’s less crowded, arguably less hectic, maybe more accessible in some ways. (For example, “off-season” visitors can enter Zion Canyon without riding a shuttle bus. The permit lotteries for cult-favorite hikes, like The Wave in Vermilion Cliffs, become less competitive.) Snow sometimes frosts the fantastical rock formations. For all these reasons, winter journeys here are on the rise.

“We’ve gone from restaurants closing in the winter to running year-round,” says Mel Rader, co-owner of Willow Canyon Outdoor, a beloved gear shop/bookstore in Kanab. “The red cliffs are usually the snow line, which means it’s pretty inviting to drive around and explore. And cold weather feels different at high elevation. It can be 30 degrees and T-shirt weather, depending on where you are. At 6,000 feet of elevation, when you’re recreating, it feels good.”

This is classic road-trip and outdoor adventure terrain. Highway 12, one of the main threads connecting national parks (and skirting Grand Staircase-Escalante’s northern edge winds past eye-popping formations and monoliths, revealing lesser-known wonders among the national parks. Red Canyon crops up out of the Dixie National Forest, its orange-pink rock formations downright jazzy among the muted pine trees. Kodachrome Basin State Park, named for the iconic Eastman Kodak color film, ironically needs no filter.

These attractions draw travelers of all breeds, from European families renting RVs for American grand tours to hardcore hikers doing the Hayduke Trail, a rugged 800-mile course linking all the Mighty Five and more. Parking lots at the national parks are an unofficial showcase of recreational vehicles, common and curious. (At Capitol Reef, folks were circling and snapping pictures of the pop-up roof of an EarthCruiser in the visitor center lot. And we’ve been Google-stalking the Italian-made Iveco we saw at Bryce ever since.) Tiny gateway towns outside park boundaries can be either downhome or glowed-up, places to find old-time diners or brand-new luxury campgrounds. Tough, lonely roads lead into Grand Staircase—tempting if you’ve got the right rig.

Above all, of course, there’s the landscape. On the road through Zion, green hanging gardens contrast with the exposed rock’s whorls of sunlit color. At Bryce, the “amphitheater” of hoodoos opens below you like a lost city, and Queens Trail and Navaio Trail lead down among them into narrow passages where bright-orange walls frame strips of sky above your path. Bristlecone pine trees, some 1,500 years old, can be found less than a mile from Bryce’s Rainbow Point.

You will want to take thousands of photos, and you will. But the most powerful moments are purely in-person. One bend in the Hickman Bridge Trail at Capitol Reef loops under a stone arch to put hikers right up close to red handprints, imprinted on the rock walls by people who lived here hundreds of years ago. The modes of travel and the reasons for the journey have changed. The power of the place endures.