On the Trail of the Exodusters

A road-trip journey in search of the lost Black history of the American Frontier.

Caleb Gayle is the award-winning author of the new book Black Moses: A Saga of Ambition and the Fight for a Black State, published this fall by Penguin Random House. The book is winning acclaim from critics and readers, including a spot on the National Book Awards long list. Here, Caleb shares a behind-the-scenes story: A tale of long drives to small towns and country vistas at the edge of the West, and the history and present he discovered there. Ride along.

Three flights from Boston brought me to Hays, Kansas, the nearest airport to a place that GPS cannot render or can’t quite find. I’d come to research my new book, Black Moses, which traces the footsteps of the “Exodusters”—tens of thousands of Black people, barely a generation away from enslavement, who migrated from the post-Reconstruction South to the Great Plains. They took their name from the Biblical exodus, a name reflecting the truth that many of these folks carried little more than the dust on their clothes as they sought out new lives in the unfamiliar West. These folks left everything known behind them to build new towns, in landscapes that must have felt to some like the end of the world.

In Kansas and beyond, the Exodusters collectively imagined something audacious: all-Black towns, governed by and for themselves. One of their most ambitious champions was a man named Edward P. McCabe, a never-enslaved Black politician who rose from Wall Street clerk to become the first Black statewide elected official in the Old West, a man who dreamed—seriously—of a Black-governed state in America.

My road trips across the Plains would follow McCabe’s trail: to Nicodemus, Kansas; to Langston, Oklahoma, the town he founded; and to the places where his vision collided with the ambitions of white settlers, Native nations and American capital.

My travels would take me to a promised land that never quite came to be: dreams of a life, unencumbered by racism, in the American West. On the road, I would discover that this dream did not vanish, but rather endured as a ghostly promise—a fragile testament of just how much was imagined, how much was lost, how little remains, and who refuses to let go.

Hays to Nicodemus

After landing in Hays, I pulled out my phone to navigate to Nicodemus, Kansas. Google and Waze offered different directions, none of which seemed precise. But thankfully, waiting on me was a daughter of the town—literally, because her family made their way there in 1877, in the thick of the Exodusters movement.

My phone blinked and buzzed. It was Angela Bates. I asked: “What address should I put into the GPS?”

She giggled. “Oh, you don’t want to do that.” She gave me her own directions. As I hurriedly wrote down street names, Bates continued at ever-increasing speed. “You’re going to want to take that to the left onto Eighth Street coming out of the airport. The next right will take you all the way through Hays. And then you take that to the town, which is called Plainville.”

Having grown up in Oklahoma, I was used to the wide-open, plain-sight vistas the Plains offer. So, when I arrived, I did what I always do when I visit family there: I tilted my head to the right, closed one eye, stuck out my left thumb, and pretended I could see what they once saw. Nicodemus drew it out of me—just like it once drew in those who took the same long, extenuating, circuitous paths to get there.

Bates continued, “Now you’re going to take a left onto Highway 18, going west again. You’re going to want to take that about 25 miles over to the town of Bogue. And then when you get to the town of Bogue, you’ll come into that town on the left-hand road and go a quarter of a block and you’ll see Main Street. You want to go to the blinking right lane and go to the grey Honda sedan and the blue pickup truck. That will be me.”

The forgettable ease with which this town could be passed by doesn’t make it any less worthy of seeking out. Nicodemus was, then as now, both the end of the world its founders fled and the fragile beginning of a new one they dared to build.

“I was used to the wide-open vistas the Plains offer. I did what I always do when I visit family there: I tilted my head to the right, closed one eye, stuck out my left thumb, and pretended I could see what they once saw.”

Nicodemus, Kansas

I had not come simply for a road trip. I came to report, to research. But what greeted me just miles from Colorado’s border was an overwhelm of history, bumping against fragile structures Angela Bates had made it her life’s mission to preserve. Angela proved so moved that someone like me, from so far away, had to come to learn this history, she started telling it to me instantly. But there was an issue. I was hungry. If not for the recorder being on, I would have captured nothing that day.

I had some forewarning from Bates’ niece, Ashley Adams, a colleague of mine, that she ran the sole restaurant for miles. I had given up meat earlier that year. But hunger pangs convinced me to indulge in what the guides with the nonprofit Western National Parks hailed as Angela’s “reigning BBQ queen” status at Ernestine’s, just across the unpaved road from her house. In hour four of what would be a six-hour history lesson, I had pictured how my stomach would adjust to what I thought would be an endless tonnage of meat.

The restaurant seemed worth a pilgrimage, carrying as it does the story of a family and the story of the town. It’s named for one of Angela’s aunts, Ernestine Van Duvall. Ernestine herself was the granddaughter of Emma Williams, one of the original 1870s Exodusters who came west to escape the whitelash to Reconstruction.

Emma was several months pregnant when she left her husband and joined her parents in the nearly 1,000-mile journey into the unknown. About 150 years later, Bates held me up from the food I wanted to eat, because of an ever-present urgency in her mind, and in the boxes full of the town’s records that filled her living room, about stories that spoke to a different way of being Black.

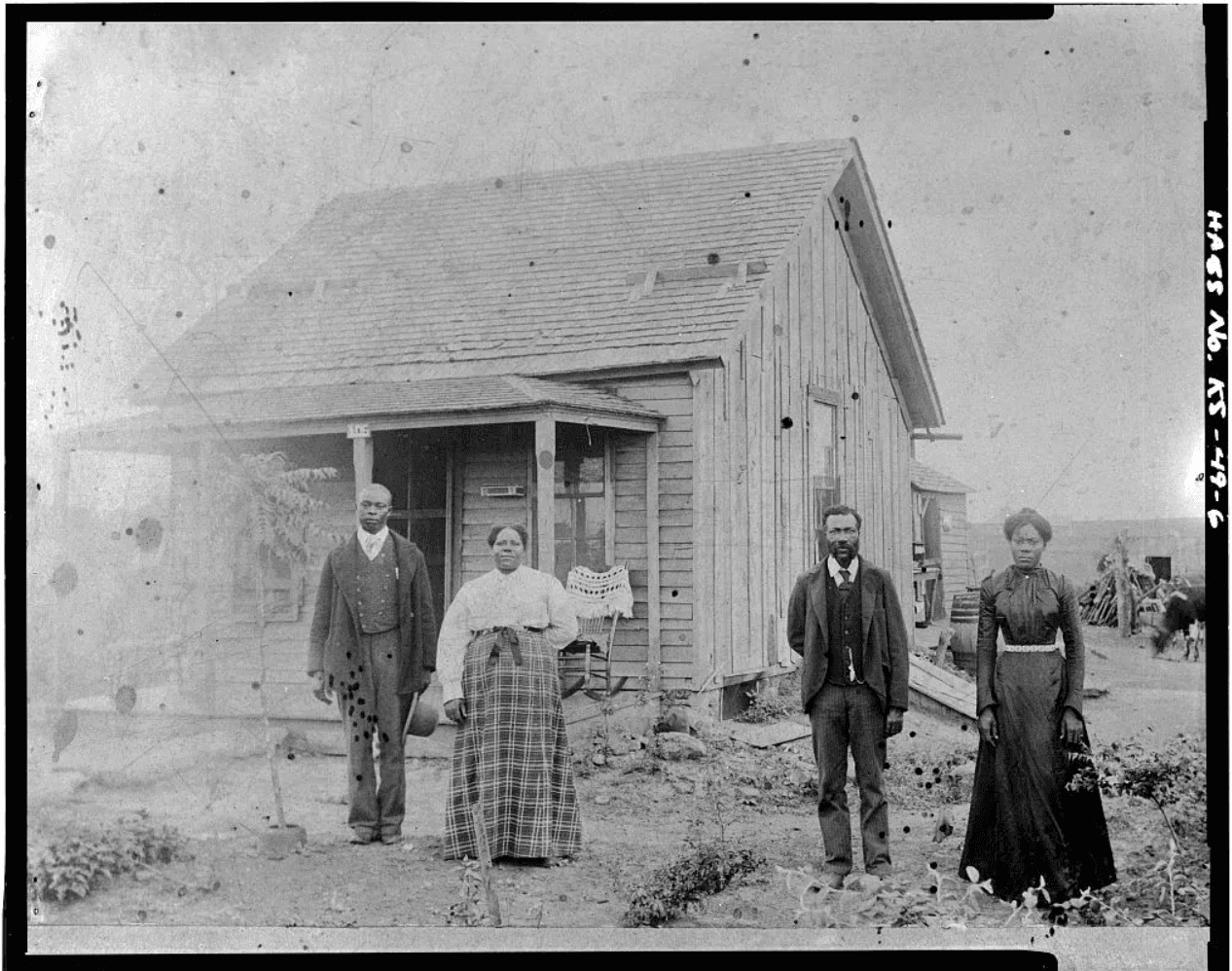

She recounted squabbles between Black Farmers’ Associations, and how the town swelled in the late 1800s under the leadership of Edward McCabe. She took me to her family’s barn on the other side of Nicodemus, which she had retrofitted to become an Airbnb. It already had guests—wasps—which would keep me company as night fell. Elsewhere I would see the near-dilapidated St. Francis Hotel, and the town’s First Baptist Church and African Methodist Episcopal Church. Without Bates, these buildings would literally not exist. She saved them by going through the tedium of having them designated as historical landmarks, working with U.S. Senator Bob Dole and Congress. Angela’s voice imbued these buildings with meaning. They were constructed only after people like her ancestor, Emma Williams, built sodhouses out of limestone, dirt and thatches of branches, in a place so far-flung that timber would be in short supply for years.

The collective burgeoning of Black citizens made Nicodemus balloon by hundreds during the early 1880s. These free, Black, voting people became a stronghold that even Kansas gubernatorial candidates needed to visit on the campaign trail.

This boom of growth owed largely to McCabe, who arrived in 1878 and brought city-slicking ingenuity to this Plains frontier, becoming a registered land licensor and attorney. He made Nicodemus and the surrounding towns his fiefdom—and a base of political support that helped him win election as Kansas’s State Auditor, not once but twice, becoming the first Black statewide elected official in the American West.

But eventually, Nicodemus’s fortunes began to fade. A promised railroad depot, which would have tethered this remote community to markets and brought new people and money in with ease, slipped away. (A selective fiscal conservatism in the state capital kept such subsidies and support from flowing to this Black town.)

McCabe lost his bid for a third term as auditor, and so he looked elsewhere. His eyes turned toward the Oklahoma Territory—organized by the federal government in 1890, the year McCabe moved there, carved out of the former Indian Territory after massive political pressure and waves of settlement—where he imagined the next stage of possibility.

My time in Nicodemus likewise came to an end, not because of its lack of hotels and restaurants (or its overwhelming presence of wasps), but because history propelled its leader, McCabe, the central point of my interest, southeast, to a town, Langston, which he would name and then pitch as the capital of something unheard of until then and still now: a Black state. And so I followed his journey there.

“Nicodemus ballooned by hundreds during the early 1880s. These free, Black, voting people became a stronghold that even Kansas gubernatorial candidates needed to visit on the campaign trail.”

Guthrie & Langston, OK

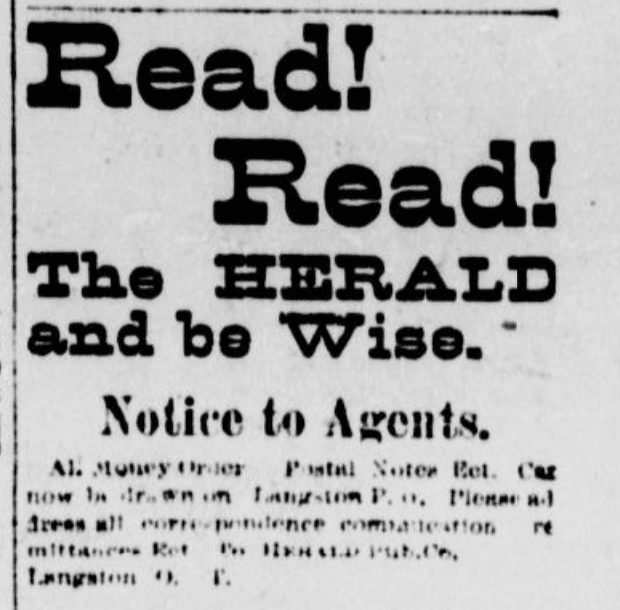

Guthrie, Oklahoma—today, a town of about 11,000—was the kind of stop McCabe’s thousands of adherents would make as they came from many places, mainly the American South after seeing advertisements in his own paper, The Langston City Herald. Others would hear from their preachers, or agents McCabe had paid—some 2,000 of them—about a Promised Land, that was everything but promised.

McCabe’s office in Guthrie still stands, with a small picture of his pointed jaw, his steely gaze behind his monocle and near-dandyish attire. I remember seeing that historical marker, back in my college days, wondering just who this Black man was with ambitions higher than most could imagine.

When I was younger, these memories didn’t contain the potency of the events of place. Had they, I would have noticed just how much the events had shaken the foundations of how we defined among many other things—identity in America, and to what degree America would dole out allowances for Black ambition. Oklahoma, like Nicodemus, offered the flat vista that enabled me to do my trick of titling to the right, my left thumb following my eyes’ gaze. I did so when I got to Guthrie. And perhaps because I was further along in my book research and writing, I began to see things that once existed, but now exist in the memories of few people, on the pages of fewer books, and in barely maintained newspaper clippings from the 19th century.

I saw McCabe, astride his horse, deputy auditor of the Oklahoma Territory, being accosted by white cowboys. They held 1873 Winchesters, the guns that won the West, so they say, on the day of the Second Land Run on September 22, 1891; they worried that this Black man would take land promised to the Indigenous just two generations prior. The land was now declared open to whoever could race and muscle their way to stake a claim. I imagined those guns firing bullets at McCabe, blowing dust and smoke in every direction, obscuring the sight of the cowboys, who had not noticed McCabe—no longer astride his horse—had just barely escaped death. I even saw the Black men nearby, who heard the gunfire and quickly returned fire of their own. McCabe wasn’t even trying to get land like these cowboys. He had already founded several towns. It did not matter to those white cowboys that he was leaving Guthrie from a day of work, unconcerned, to head back home in Langston to his family.

I also imagined the hundreds of Black people coming into Guthrie, hunkering down in the Black section of the town, which was nothing permanent, just an itinerant weigh station, after sitting in train cars designated as Negro. I saw the depot—for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Rail Company—still standing on 409 West Oklahoma Avenue, as both a historical marker of inclusion and exclusion. The rails carried in dignitaries and world leaders, but relegated Black people to substandard cars. I saw the inequity that sparked the ire of McCabe, who thought himself something of a Moses, and who filed a lawsuit (McCabe vs. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Co.) that took him to the U.S. Supreme Court, sacrificing his own wealth to fight a losing legal case for Black people to sit in the same rail cars as their white peers.

I saw in Guthrie’s town center, minutes from his office, where McCabe lobbied for what they called “fusion” to his fellow politicians, men he had helped lift to office, who now refused to lift him back. Fusion—what you and I would call equal treatment, especially for Black children in schools—was, to them, a threat. I saw ambition cut down, not abstractly but violently, in the town square—McCabe bum-rushed from the stage, his Black allies caned, the authorities summoned not to protect but to punish.

I saw, too, the office of the Guthrie Leader, the paper of record, where in 1908, McCabe returned—nearly penniless but proud, years after his Oklahoma political career ended—to pay a $10 debt. “Yes, I’m leaving,” he told them as tears glistened in his eyes. “I want to be even with the world,” he said. “I’m settling everything I owe. I love Oklahoma, but the new state has grown too fast for me. I must seek other fields.” (For McCabe, those fields were in Canada, a country that had already tried to stem the heavy tide of Black people crossing over from Kansas, Oklahoma, and the South.)

And still, I saw him refuse to be bitter. “I shall not complain,” he said, “and I have no advice to offer my race. Oklahoma has been good to the colored people and it always will be as long as they are orderly and law-abiding.” I saw a man trying to leave even, but knowing history would never let him settle the account.

I had been to Langston, Oklahoma, not far from Guthrie, before—many times, in fact, during college. I went to the University of Oklahoma, a short one-hour ride from Langston. If you look on a map of Oklahoma, you’ll see that Langston sits just half an hour from the border of the state’s capital, Oklahoma City. And though it might seem that not much is there, like Nicodemus, it is suffused with Blackness in a way so rural, yet so metropolitan in its aspiration. Langston, a town founded by McCabe, is home to a university also founded by McCabe, named after John Mercer Langston, a Black two-time ambassador, congressman, and contemporary of McCabe. The names of the streets evince big homages to Black people who had achieved: Bruce Street, named after Blanche Bruce, the country’s first Black elected U.S. Senator to serve a full term (another McCabe contemporary).

As a college student in Norman, a town that in our parents’ lifetime had been a sundown town, Langston seemed like a quick break from the overwhelm of whiteness. Parties inside Gayle’s Auditorium (their gym) didn’t have the overpolicing that seemed to hover over the Black parties at the University of Oklahoma. There was no additional proverbial tax to be paid for being who we were in the way we wanted to be.

So, the drive to Langston to meet with its mayor, Michael Boyles, and his de facto chief of staff, his wife, Mary Boyles, was an endless playlist of memories, set against everything I had learned about the man who made this town.

I entered the mayor’s office, which sits inside of the town hall. It had few of the trappings of the town halls you might know. Yes, there are pictures of the mayors who presided over the town, stretching back to McCabe himself. Yes, there’s an American flag, the state flag, and a commemorative plaque of this building’s history. But the drive up to the town hall revealed what I had come there to discuss with the mayor: many roads weren’t paved, and those roads that were paved had suffered under a lack of resources to smooth them. And the mayor and the mayor’s wife were bent on paving them even if the funding wasn’t there. In some sense, these two are fighting the same fight McCabe fought, even if he knew that ultimate victory might remain ever-elusive.

Here, in this all-Black Oklahoma town of Langston, McCabe’s ambition had crystallized into streets and buildings, a university, and a community—his tangible response to America’s often elusive promises of freedom and equality. His vision took root even if his own time there withered.

I could feel those echoes still alive—in the rough gravel and compacted dirt beneath my tires, in the weathered yet resilient buildings standing proud, bearing witness to dreams that didn’t die, only adapted. The mayor and I sat together in the humble office, no sunlight slipping in through the windowless room, plastic folding tables substituting for the conference room tables one might be accustomed to.

He and Mary spoke passionately about their "Pave the Way" program—symbolizing not only improved infrastructure but also a lasting recognition and dignity long overdue. The history they so carefully protect and preserve here isn't grandiose or monumental; rather, it's personal, intimate, and often fragile—captured in stories whispered from generation to generation, letters tenderly preserved, and faded photographs that vividly reflect the faces and lives of people who dared to believe in a dream far greater than mere survival. To accomplish this, they’re selling the streets that they’ve determined to have enough important historicity, selling to the highest bidder, and offering them the name of the street. And with that earned revenue, they’d pave the streets, the ones that even though I had visited many times before, had histories that I had bypassed.

Perhaps this, after all, is what it truly means to journey to the end of the world. It's not merely about reaching some distant physical destination; rather, it involves arriving at a deeper understanding of the enormous cost dreams can exact. It means seeing clearly and acknowledging the profound gulf that often separates our ideals and promises from stark realities. Edward McCabe, like Moses, his colloquial namesake, never entered his Promised Land, the full realization of his dream—his political ambitions were ultimately thwarted, his resources nearly entirely depleted. Yet, his legacy undeniably remains alive and vibrant in these communities, preserved in the quiet dignity of the residents who continue to build meaningful lives here, and in their persistent, unwavering belief that his dream was—and perhaps still is—entirely worthy of pursuit.

As I departed Langston, the vast flat lands unfurled endlessly before me, a sea of grass and sky stretching infinitely. I got out of my car at the nearest gas station in Guthrie, tilted my head slightly to the right, stuck out my thumb, and imagined, yet again, however whimsically, that I could indeed see hundreds of miles into the horizon, where land and ambition intersected. In that moment, I understood, perhaps more clearly than ever before, that the end of the world isn't truly an end at all. Rather, it's a perpetual beginning—a horizon forever under construction, shaped continuously by dreams deferred but never completely surrendered.

Caleb Gayle’s book Black Moses is available now. For more of his writing, visit calebgayle.com.