Ashtin Paige

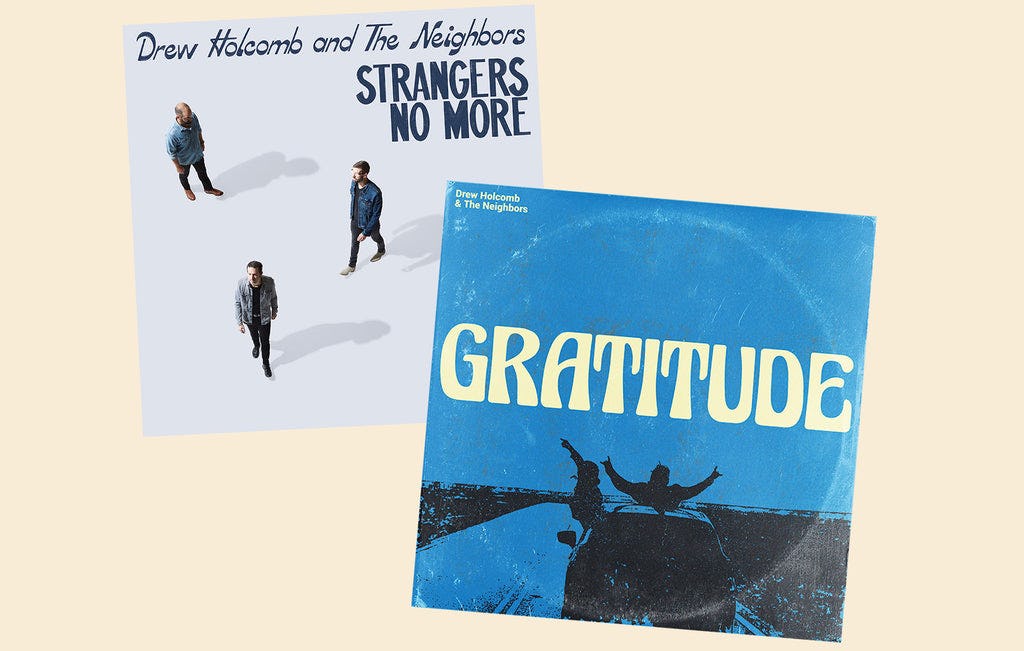

As the singer-songwriter toured his 14th album, Strangers No More, and prepared top perform at the Moon River Festival [which he founded], Wildsam asked him a few questions about Tennessee, music festivals, decades of songwriting and why he loves to fly.

Wildsam: How has being from Tennessee influenced the direction of your career?

DREW HOLCOMB: I’m a fifth-generation Memphian on both sides. It really has its own culture, its own history, its own chip on its shoulder. And I mean that in a good way. I think there’s a sense that people look down their nose at Memphis, because it’s got a variety of challenges. Memphis taught me a little bit of this contrarian and independent streak.

When I came to Nashville in 2006, the live music culture was very industry–nobody moved up front at the show, everybody stood with crossed arms. It was an insecure place. That was good soil for me to create in, because I did it my way. For instance, everybody was telling me I needed to record with studio musicians, not my road guys. From the outset I said, "No, that’s absolutely not the way I want to do it. I’m going to record with my road guys, and they’ll become studio musicians," which is what’s happened. I’ve been with them ever since. And now they’re very high-demand guys.

The thing that Memphis did poorly, that perhaps Nashville did better, is that Memphis continued to trade on what happened back in the ‘50s and ‘60s and ‘70s with Elvis and Sun Records and Stax–which is awesome, but there wasn’t a lot of avenue for development as an artist. Where as Nashville is like, "Hey everyone, come here."

Can you talk about that evolution–Nashville’s rocketship growth, for better or for worse?

It’s both, honestly. You could eat out 365 days in Nashville and have 365 different and great food experiences. That’s special. Part of that’s the immigrant culture here, and part of it is the melting pot that happens when people move from all over the country. Like Austin and L.A., Nashville also has an extremely high rate of self-employed creative people, so there’s an energy, which has also affected my music and, I think, made me more pro. I also hate to leave Knoxville out, because that’s where I started writing songs.

How did that eastern part of the state influence you? You went to the University of Tennessee?

Yes, I went to UT. Knoxville has a great folk history. We would take weekend trips to Bristol to go see the Carter Family Fold, which is where country music really got its start. And then we’d take trips over the mountain to Asheville to go to Jack of the Wood to see old-time string bands, and then go to the Orange Peel, and then down to Chattanooga for shows.

That is such a unique stretch–a straight line, east to west, Asheville, Knoxville, Nashville, Memphis. And of course there’s legit music history from the Shoals and the Delta. Any explanation of what’s going on with that geography of music?

I don’t know. I’ve always had a thesis about the Mississippi River with New Orleans, Memphis, St. Louis, Chicago, Minneapolis as another music line. It’s like a Cattywampus cross. That north-south one is easy for me, because of the river. People were traveling up and down it. Then when Elvis moved to Nashville, it sealed the fate that rock 'n' roll and country were going to have this incredible meld into popular music.

The irony is the majority of what I was listening to when I was a kid had nothing to do with the history in Memphis. It was Pearl Jam and U2 and ‘90s rock radio. But that history, even if you’re not paying attention to the local zeitgeist when you’re 13, 14 years old and learning to play guitar, it’s there. And you can’t help but be caught up in it eventually.

Can you chart a moment as an artist when you stepped into your own as a craftsman?

I think the first record we made that felt like what I wanted to sound like, and what I want the songs to feel like, was Good Light. I’m proud of everything on that record. It felt like a complete creative and independent statement. It came out in 2013, so that was nine years in. Some artists make their best work when they are really young. It took me a minute, and that’s okay. Red Headed Stranger came out when Willie Nelson was 43 or whatever, so I feel okay about it.

Are there songs in your catalog that immediately register a certain place for you?

Off Good Light, “A Place to Lay My Head,” shows you a state of mind. I wrote that in a hotel room in San Diego, just feeling all of the loneliness of travel. “I’ll Never Forget The Way You Make Me Feel” registers the Ryman Auditorium for me. The first lines of the song say "I might forget what you wore on the 14th day of May." That was my first date with my wife in 2005 at the Ryman. We saw Patty Griffin.

Also, “The Wine We Drink” takes me to my kitchen because I wrote it one night thinking about how the monotony of marriage is actually where the magic happens. “Dirty dishes in the kitchen sink,” I wrote while sitting in the kitchen by myself one night when Ellie was away.

“Rowdy Heart, Broken Wing,” off Souvenir, I wrote in an airport hotel in Amsterdam waiting to fly home after a three-week European tour. I’d gotten news that my brother had a little bit of a relapse. He’s now been sober for six years, but he had just started trying to get sober. I wrote that song from his perspective, I was looking out over the Amsterdam airport in the rain, just overwhelmed with sorrow for him.

Another one off that record “New Year” I wrote on New Year’s Day, the morning after a party we have every year. I had this moment where I was pretty juiced up on some great wine, looking around the room, everybody’s having this awesome time, but I’m also looking at all my close friends and knowing there’s four or five really tough stories happening in their lives while we’re in this party. I wrote the song about those friends. "It’s a new year, it’s a new song. It’s the same mystery." Life is amazing and so tragic all at the same time.

How about the new record?

“Dance With Everybody” happened after I was in line to drop my kids off at school. I ran into my friend Ketch Secor from Old Crow Medicine Show. His kids go to school there as well. He says, "What are you doing this morning? Want to write a song?" We went to get some coffees, and we did just that. We started talking about how great it was to be back on stage. We had finally both had our own tours post-COVID, and we were talking about how magical that was compared to the weirdness of the livestream era. “Dance with Everybody” is an ode to the audience. It’s a song about the live show. "And when you walked into this room, you hardly knew anyone. A sea full of strangers crashing on the rugs. When the band strikes by the end of the night, strangers no more, I want to dance with everybody who came through the door." We wrote it in 45 minutes.

The sentiment obviously is important to the album, since you put it on the cover.

Yeah. It’s a record about how important community is in the face of tragedy, chaos and the insecurity of being a person. Songs like “Free, Not Afraid to Die” is the song I wrote after I got meningitis, and I was in the hospital for eight days, and I thought I was going to die.

When was that, Drew?

That was 2017, but it took me three years to process it, four years, and during COVID I really started to become comfortable with my recovery from that fear. It’s just a song about letting go of grudges and being excited about getting older in spite of everything. “That’s On You, That’s On Me,” it’s a song poking fun at myself and everybody else, in the way we create our own mythologies, about how we instinctively create narratives to make our lives more meaningful, and how that’s really a beautiful thing, even though it’s also incredibly selfish and hilarious.

The Moon River Music Festival, which you founded–how did that come to be? How is playing festivals unique and important to your work?

I have to start with my love of music festivals as a fan. The big event in Memphis as a middle and high schooler every year is Beale Street Music Fest. It’s always the first week in May, two or three weeks before the barbecue fest. It’s a classic city fest, meaning that it’s a cheaper ticket. It’s slightly subsidized by the taxpayers, and they bring in everything. I remember my senior year it was Lynyrd Skynyrd and Three 6 Mafia on opposing headline stages.

That’s the South right there.

The South in a nutshell. I remember the first time I went. End of my freshman year, my buddy and I were 9th graders and got invited by two junior girls to go see the Wailers and Ben Folds Five. I just had this great experience as a fan. I knew Ben Folds Five’s music. I knew the Wailers “No Woman, No Cry,” but I didn’t really know. We saw a bunch of other bands that day, so there’s this discovery piece. There’s life on life, sweaty bodies, people eating fried food–just the magic of community that happens at a music festival. In college, I started seeking them out. My senior year, I came to Austin City Limits when it was REM and Al Green. I caught one of Al Green’s roses. This lady’s like, "You got to give me that rose," and I was like, "Not a chance, ma’am. This is my rose."

When I started playing music, I really wanted to get invited to play at festivals, and it took a long time finding our place and getting to that point in the sense that we were pretty mellow for those first few records. We played Bonnaroo in 2013. It was awesome. My daughter was six months old. Her first show beside me was Paul McCartney.

Holy smokes.

Since then we’ve played everything. Stage Coach, Austin City Limits multiple times. Man, there are so many. We just played Wichita River Fest, which is all genres. It's all walks of life.

Then you have the big marquee festivals, like the Bonnaroos, the ACLs, and they are awesome, but the scale is so intense, honestly. They’re a bit intimidating. Sometimes you feel like you’re just a cog in the wheel or just another band. Then some of those same promoters do things like High Water and Moon River now. Moon River only has two stages, so you never are competing with another band. It came about as an artist-curated festival. There’s one in Virginia called Red Wing and Roots Festival, started by a bunch of bluegrass bands. Back when I started Moon River, Mumford and Sons had just done the Gentleman of the Road series, where they were doing these popup three-day events with 20 bands all over the country. Then Lucero was doing this thing every year called the Family Picnic. Grace Potter had one called Grand Point North. Now The National has one, The Revivalists have one.

Would Willie Nelson’s Luck Reunion be considered an artist-curated festival?

Luck Reunion would absolutely be. It’s obviously tied in with South by Southwest to a degree, but the idea that an artist says to their audience, "Hey, I want to put on event that feels like, smells like, sounds like me, and I want to introduce you to these bands that I love and I want you to trust me, so buy ticket and come to this thing." That’s how Moon River started. It was a smaller event in Memphis for three years, and then it got to be more than we could manage, That’s where AC Entertainment said, "Well, we would love to take it over and partner with y’all, but how would you feel about moving it to Chattanooga? We feel like it’s a better spot for what y’all are wanting to do long term." Part of that’s just geography.

If I’m going to a festival, what’s a good hack for the best experience?

If you have a friend in a band playing, be a part of the crew, so you can go experience all the hospitality.

Also the best place to stand is near the sound guy. The closer you can get to the soundboard, the better. Up front, right by the front, the sound is not going to be nearly as good. Get back 30, 40 feet near the soundboard, and that’s where it sounds awesome, and you can see the whole thing. You’re experiencing the show visually and audio-wise exactly how the band wants you to experience it.

Are there festivals that happen in a unique place in America that you’d recommend?

BottleRock is a very special one because you’re in the beautiful California wine country. We’re really excited about Bourbon and Beyond, which is in Louisville, and they really lean heavily into the food and bourbon space. I’m not trying to sling tickets, we’re sold out, but I think Moon River is one of the more unique festivals, because it’s in the city. You can stay in a hotel, walk back and forth. You never have to take a shuttle. You can bring your kids, you’re never going to compete for music. It’s manageable, because there’s only ten or twelve thousand people.

One of my favorites is actually the cruise. Cayamo. If you love all the great songwriter artists, you get to see 30 shows in seven days, and you’re going to bump into them. That's how I met Jeff Tweedy. I knew Mavis Staples because she had played Moon River. She’s on Cayamo, and they had an artist party on the beach one day, and she’s sitting there eating lunch with Jeff and my band sits down at a table nearby. She looks over and goes, "Hey, Drew, come here." And I was like, "Hey, Mavis, what’s up?" She goes, "Do you know my friend Jeff?” And I’m like, I just got to meet one of my hero artists, Jeff Tweedy, and who introduced me to him? Mavis Staples.

Can we talk about flying? When did being a pilot start for you?

I actually got my license in college, so I started flying at 18. Then I took a 15-year break.

My grandfather was a Naval aviator in World War II. My great-grandfather was in the Army Air Corps, now it’s the Air Force. His weekend job in his ‘30s was teaching people how to fly bi-planes in 1929. When my grandmother was five, he died in a plane crash. His widow, my great-grandmother lived to be 99, and she lived with my grandparents five doors down the street from us. I was 15 when she died. She was our main babysitter for my childhood. I’m one of 28 grandkids, and no one had learned to fly, and I thought, "I’m going to break the fear, the hex.” I had an appointment at the Naval Academy and was going to go and fly, and I got a cold feet. So I went to Knoxville and made a deal with my dad. He said, "If you go to UT and take the scholarship, I’ll pay for you to learn how to fly.” I got my private license at the very beginning of my sophomore year, and I flew for four years for fun, not a ton, maybe a couple hours a month, and then gave it up because I ran out of money and time. Then during COVID, Ellie let me get back into it. I finally had some time, and at this point in my life, I had the means. I found a club, 15 Pilots, that shares a couple planes and makes it financially doable. Now I fly a ton.

What I love about it is two things. One: You’re in the air, flying above the ground. I can’t think of any other way to describe it than magic. Every time I do it, I can’t believe it. I just love it. And two: It’s one of the only places left where you can’t be on your phone. I hated it when the airlines got the internet, because that like my sacred space.

Now, when I’m flying myself, I just let my thoughts wander and go wherever they want to go. In more ways than one, flying is like a time machine.

The Wildsam Questionnaire

What’s the best way to start your day?

Couple of squats and three things you're grateful for.

What's one place you’ve never been?

I have never been to Egypt.

What sensory experience do you most associate with your hometown?

Laughter. Fifty people in someone's house. Everybody talking over each other. The sound of family.

Mountain, desert, or sea?

Mountain.

Your dream vehicle for a cross country drive?

I would love to do a 50-state RV trip.

Where would you go to disappear?

Up in the air. I’d go up on a long flight.

Gas station snack of choice.

Used to be a Little Debbie Nutty Buddy. Now I've grown up a little bit, it’s a bag of cashews.

Do you have any life advice you’ve never forgotten?

I always got in trouble if I didn't swing at the third strike, so Dad’s advice was “Go down swinging.”

Your favorite word?

Gratitude.

What’s one place that fits your personality?

Telluride, Colorado.

What do you want to be when you grow up?

I’d love to be a musician, who’s also a pilot, who plays a little golf and travels with his kids and his wife. So I guess I'm all grown up.

What’s the song you want to be on the radio when you get in your car today?

“Born to Run” by Bruce Springsteen.