Where Jazz Thrives in New Orleans

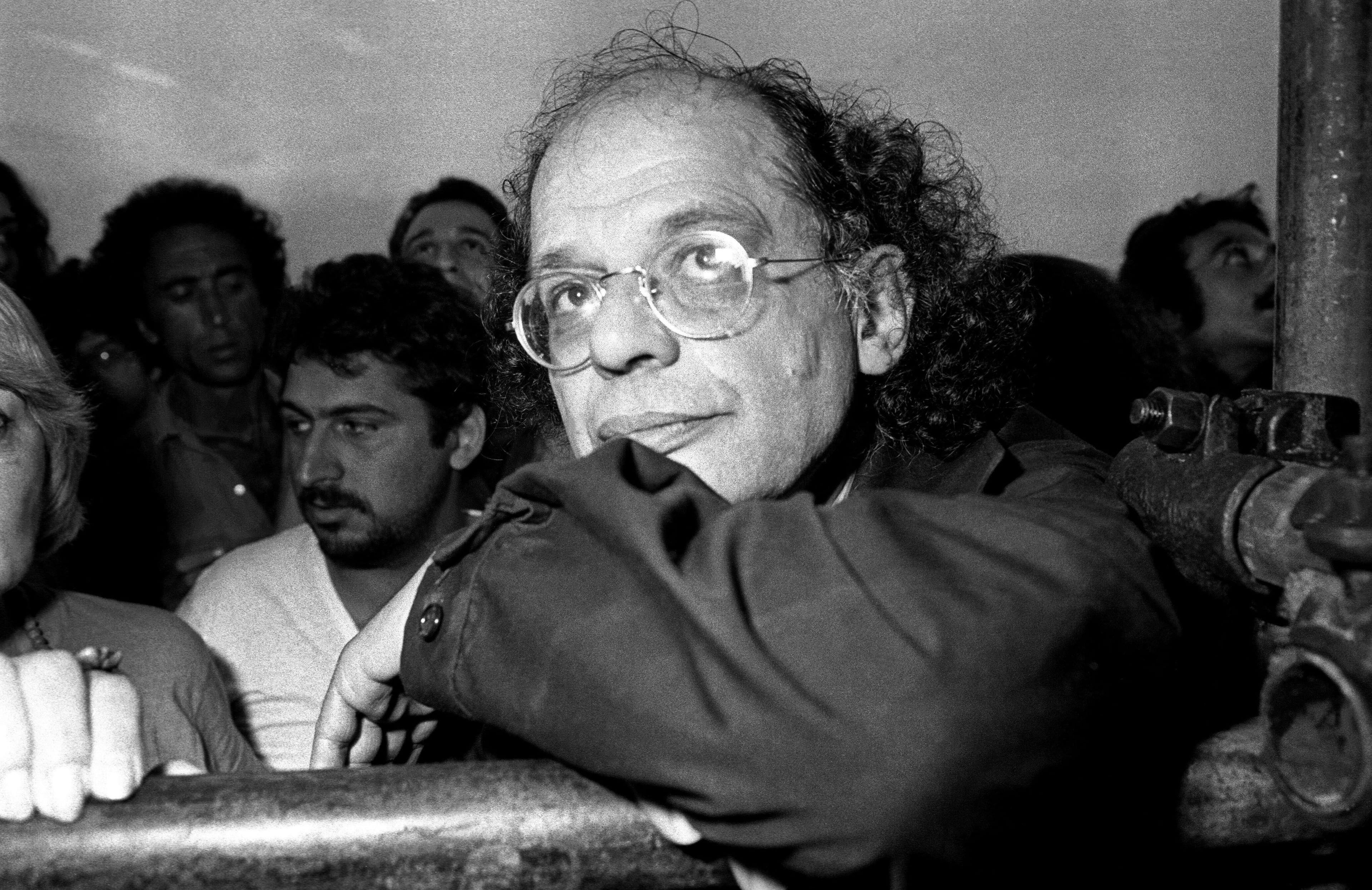

Jason Marsalis live at Snug Harbor.

From Preservation Hall to Maple Leaf Bar, jazz in the Big Easy is constantly reborn.

MUCH HAS BEEN SAID about New Orleans’ glacial pace. Minutes stretch like taffy, past dances with present. It would all be cliché if it didn’t remain true. Amid old traditions and shotgun cottages in every color of the crayon box, it’s easy to see the city’s native music, jazz, as similarly antique.

“A lot of people outside New Orleans perceive the scene here as people exchanging the same songs and studying old material,” says Jason Marsalis, youngest sibling of New Orleans jazz’s first family, including brothers Wynton, Branford and Delefaeyo and patriarch Ellis. “They think of it as one thing and put it in this box.”

In the spring, thousands of music-lovers head for the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. Of course, that’s an amazing event. But finding New Orleans jazz in its real, ever-evolving forms requires more exploration. The key, according to Marsalis and other mainstays: improvise. Catch the streetcar to that spot the bartender recommended. Listen for the latest listings on WWOZ. Don’t pass up younger artists or lesser-known names.

Yes, there’s much to be said for the French Quarter and its many clubs. At the most revered of all, Preservation Hall, some of the city’s most gifted musicians play traditional jazz every evening. But just as a richer sense of the city in general emerges beyond the Quarter’s edges, venues across town present a fuller sound.

Further east in the Marigny Triangle, Marsalis performs regularly at Snug Harbor on Frenchmen Street, where he first played at when he was just eight years old. “Every Saturday my father had his quartet, and I’d come and sit in on a tune or two,” he says. “I’m still here. We're still doing it.”

While many of Frenchmen’s clubs have broadened their acts beyond jazz and blues, Snug Harbor endures as a home for local legends like Dr. Michael White and Herlin Riley. “That spot needs to be preserved,” says Xavier Reed, a musician and jazz department chair at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, a conservatory high school. “If people come from New York or Morocco, they’re playing at Snug.”

When Reed isn’t teaching, he’s watching the orchestra at The New Orleans Jazz Market in Central City or seeing mentors swing at Bayou Bar. The Pontchartrain Hotel’s bar opened in 1947, and a 2016 renovation brought its cypress-streaked murals back to life. Now it’s one of few intimate spaces that consistently host jazz from masters like Johnny Vidacovich and more modern players like Pedro Segundo.

New Orleans

Live music and neighborhood bars, preservationists and culture bearers, hidden courtyards and legendary restaurants.

Acclaimed bassist James Singleton arrived in New Orleans in 1971. “My introduction to the traditions in New Orleans was from people 30 and 40 years older than me, and I often played with many generations at the same time,” he says. “It’s really thrilling to look around the bandstand and realize that everybody could play at Preservation Hall and do the traditional style. Sometimes we’ll throw in one of those pieces, and it’s exciting because it’s so unexpected. You end up getting a different take on the traditions.

Singleton strums in many projects at Snug Harbor and newly opened outdoor venue The Broadside. He has also been a longtime staple at the storied Maple Leaf Bar, once the haunt of the piano savant James Booker. With music every night, the bar brings locals and determined visitors alike way uptown to New Orleans’ outer edge—a celebrity sighting there isn’t unheard of during Jazz Fest, either. And often, the music Singleton and others play there sounds very unlike “New Orleans jazz.” He says that’s exactly what makes it New Orleans jazz.

“The traditions were not traditional when they emerged,” says Singleton. “When King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton were doing it, jazz wasn’t traditional. It was something new and exciting and scary. And that’s what I like in my music.”

WHAT TO KNOW AND WHERE TO GO

Snug Harbor Jazz Bistro

Marsalis and Singleton play often.

626 Frenchman St, snugjazz.com

New Orleans Jazz Market

Ensembles in a roomy theater setting.

1436 Oretha Castle Haley Blvd, thenojo.com

Bayou Bar

Cozy, warm, often two shows.

2031 St Charles Ave, bayoubarneworleans.com

The Broadside

Indoor-outdoor, multigenre.

600 N Broad St, broadsidenola.com

The Maple Leaf

Legendary. Brawny talent nightly.

8316 Oak St, mapleleafbar.com

Preservation Hall

French Quarter throwback staple.

726 St Peter, preservationhalljazzband.com

The New Orleans Jazz Museum

Lends historical perspective to the global creative forces unleashed here.

400 Esplanade Ave, nolajazzmuseum.org

WWOZ

Stalwart nonprofit station that can serve as a 24-7 teleporter to New Orleans wherever you are, maintains its crucial live-show listings at wwoz.org/calendar/livewire-music

Read more like this