Fandom in Philly

Philadelphia sports fans know you don't like them. They're way too resilient to care.

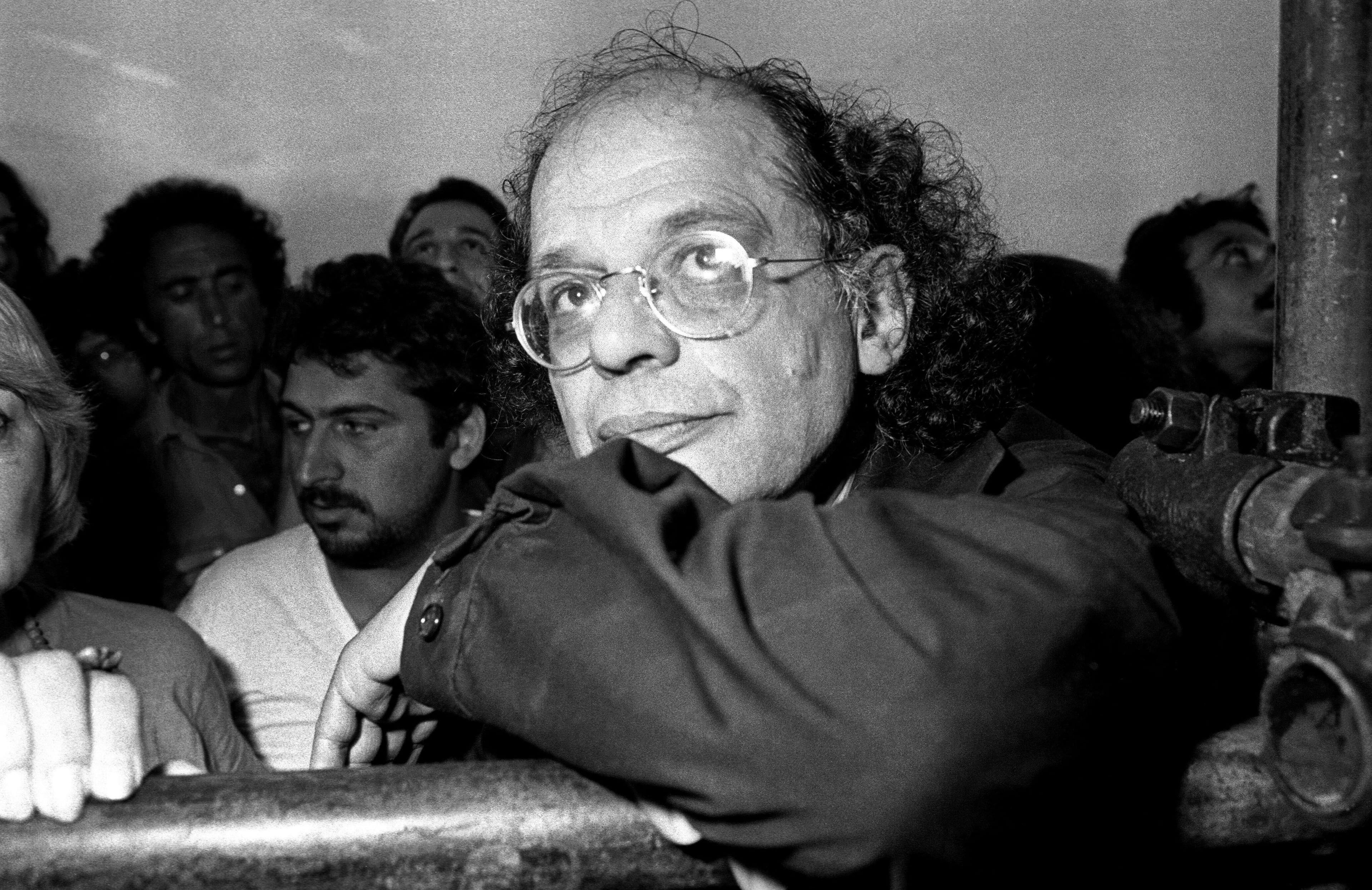

Eagles Fans | Casey Murphy

I CAN’T REMEMBER the occasion for which I first heard Philly’s unofficial theme song—sung to the tune of “Found a Peanut,” most likely by a crowd of drunk Eagles fans—but I do remember thinking it was f—ing depressing. Growing up outside the northeast boundary of the city, I was a self-conscious kid whom the popular kids occasionally sniped at but mostly just ignored. I couldn’t imagine a scenario in which I would willingly announce to the world that no one liked me, even if I often believed it to be true.

I took refuge in the emo and punk scene at the city’s Electric Factory warehouse, where my friends and I shouted for Dashboard Confessional and Alkaline Trio. We skipped school to see the Dalí centennial at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, walked South Street at dusk, gorging ourselves on water ice and dreaming up the tattoos we’d get when we turned 18. Everyone I knew (myself included) was proud of their working-class roots, but in the hands of teenagers, this pride was quickly bastardized into the notion that being a good student was uncool or somehow disloyal. And I was undeniably a nerd, always with my head in a novel, writing secret poetry, bumbling through the school play because I knew that at least the theater kids would talk to me.

Finally, I graduated high school and made a break for it—no more treading water in a stagnant city where the subway still inexplicably ran on tokens. I went to Boston, then New York City. And I stayed away for a long time.

On the surface, there’s a lot to dislike about Philadelphia. It’s always been filthy, dirtier still after yet another deep cut to the sanitation budget in 2009 eliminated street cleaning. It’s dangerous here, with pockets of the city leveled by the opioid crisis, and far more murders per capita than New York City or Los Angeles. It’s poor—the poorest large city in the United States, with 25 percent of residents living below the poverty line. A deeply tangled chicken-and-egg mess of political cronyism, failing public schools, the loss of over 300,000 manufacturing jobs in the latter half of the 20th century and the unrelenting crush of systemic racism and mass incarceration are to blame.

In some ways we’re a city marooned. Though Philadelphia and New York are less than 100 miles apart, public transportation between the two leaves something to be desired, with the schedules for SEPTA’s Philly to Trenton River line and NJ Transit’s Northeast Corridor sometimes failing to line up at all. Many surrounding suburbs have crafted zoning ordinances that block the construction of affordable housing units within town limits, cementing a classist and often racist divide between the city and its suburbs. For its part, the state of Pennsylvania has held tight to its foundational Quaker values, namely a laissez-faire approach to government (except where alcohol is involved—then the grip is vise-like). As a result, economic growth in Pennsylvania is at only half the rate of the rest of the country since the Great Depression, a statistic so stark that it’s difficult to argue it’s anything less than intentional. But what works for the rural and agrarian parts of the state leaves an urban center like Philadelphia hamstrung.

No surprise, then, that feelings of abandonment and the city’s struggle to keep up with its neighboring metropolises have led to some sizable chips on the shoulders of its residents. My husband likes to say that Philadelphia suffers from Little Brotheritis, being so near to New York and Washington, D.C. And Philadelphians certainly do play the class clown for attention, making headlines for pelting Santa Claus with snowballs, throwing pool parties in dumpsters and stealing police horses. Though the city was once the economic and political epicenter of the nation, today only about a quarter of Americans can correctly identify the Philadelphia skyline. And somewhere along the way, it seems Philadelphians decided it was better to be infamous than forgotten.

But I like to think maybe we’re just misunderstood. The blue-collar culture that feels gruff to outsiders is really just a no-nonsense approach to communication. More than that, underdoggedness is axiological to this city since its founding. Philadelphia was once the gathering place of radicals plotting to overthrow the British crown, and George Washington turned the tides of the Revolution on the Delaware River just north of the city limits. Later, the Civil War and the Great Migration made the first free city north of the Mason-Dixon a hub for abolitionism and communities of formerly enslaved people. Today, it’s a boon for fresh waves of immigrant and refugee populations from Latin America and Southeast Asia who’ve injected the city with new life. This includes founders of new Philly-based tech and health care startups like GraphWear and Haystack Informatics, and culinary heavyweights in an already food-famous city, including South Philly Barbacoa’s chef, Cristina Martinez (featured on Chef’s Table), and Ange Branca, a James Beard Award semifinalist for her Malaysian fare.

I remember the first time I missed Philadelphia, really missed it for the city itself, beyond a vague homesickness. I was in Manhattan with a new group of friends much worldlier and wealthier than I was. Usually when we went out, a combination of necessity and obstinance meant I wouldn’t eat, not wanting to blow what I knew I could stretch into a week’s worth of food money back home on a single meal. (As it turned out, I’d absorbed more Philly attitude than I cared to admit at the time.) But I felt a glimmer of hope the night one of them suggested we go down to Little Italy for dinner. I envisioned the bustling Ninth Street of Philadelphia’s Italian Market—its fresh produce stalls, butcheries and cheese shops, porchetta sandwiches, pizza windows and pasticcerie. If Philly’s Little Italy was undeniably great, how much more amazing would New York City’s be? Better yet, something there would be affordable, and I would finally get to eat dinner, or at least fill up on water ice. But when we arrived on Mulberry Street, there was almost nothing there—a few sit-down restaurants and a few strands of red, white and green fairy lights to mark the ghost of what once was.

A slow rate of change can be frustrating for Philly residents, but it also means a melding of old and new unique to this city—in other more rapidly gentrifying places, historical sites and cultural hubs might have been razed to make way for oligarchs’ condos. Places like the Italian Market, which dates to the 19th century and remains one of the oldest and largest open-air markets in the U.S. It’s not only still bursting with great Italian food but is also home to an influx of other international flavors, including Martinez’s tacos and enough Vietnamese food to earn the alternate nickname “Little Saigon.” In Manhattan, Little Italy was subsumed by Chinatown. Here, we have the space, affordability and rooted communities to keep the best of both.

I moved back to Philadelphia in 2017, just in time to see the Eagles make their Super Bowl run. Every game, I’d walk over to a high school friend’s house to crowd on the couch and watch. More of a baseball fan myself, I’d never really liked the stop-and-go nature of football, but this city’s love for its Eagles is nothing if not contagious. And there was that song again: Whenever they scored a touchdown, someone would head off the Eagles’ official fight song, which flowed right into “No One Likes Us.”

A version of “No One Likes Us,” it turns out, was originally a soccer chant for the English team Millwall, set hilariously to the tune of Rod Stewart’s “Sailing.” Millwall fans took unruly to another level—in the 1960s, one even threw a grenade onto the pitch. The Philly adaptation of the song also grew out of a soccer fan club, the Sons of Ben (as in Franklin), who formed online before the city even had a soccer franchise and who now cheer on the Philadelphia Union from the river end of Subaru Park.

But the song made a home for itself far beyond soccer, and as the Eagles’ success continued through the playoffs that year, it was a staple in the bars and city streets. Then our star quarterback, Carson Wentz, tore his ACL. It was up to second-string Nick Foles, who hadn’t played that season, to take on Tom Brady and Bill Belichick’s Patriots, one of the winningest teams of all time.

When the Eagles won, the fans flooded the streets and all manner of stupid behavior ensued. The national media tore the city apart, but then again, didn’t they always? What looked like chaos from the outside was the most harmonious I’d ever seen the city’s residents. A few days later, the team threw an officially sanctioned parade. Our apartment at the time was on the route, and our friends showed up early to claim space on our stoop. I poured coffee for the cops who’d come in asking to use our bathroom. Our upstairs neighbors had painted a bedsheet with the phrase “Big D–ck Nick”—the city’s nickname for Foles—and hung it out the window. As he passed by on the double-decker bus, Foles laughed and snapped a picture.

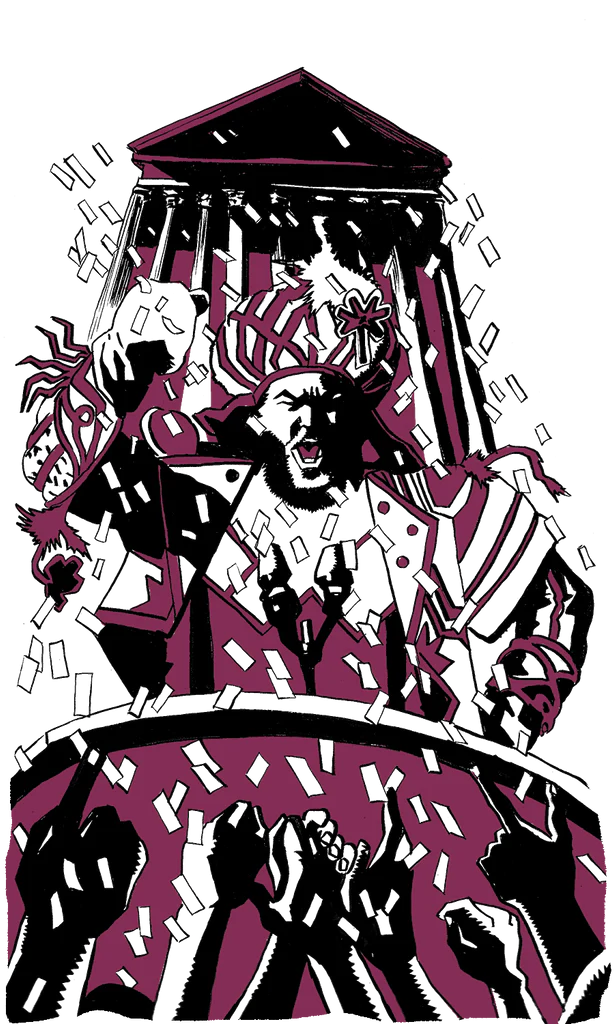

The parade ended at the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where the team’s center, Jason Kelce, clad in a Mummers suit and hat, presented a laundry list of negative things people had said about the Eagles and the odds they’d overcome, then led a million-person singalong of “No One Likes Us.”

In that moment, Kelce embodied the essence of the city beyond football: His sequined outfit is the traditional celebratory garb of the city’s large populations of Ellis Island-era working-class immigrants, his place on the museum’s steps a callback to the city’s favorite claim to fame: Rocky Balboa. For a moment, Philly was the top dog.

Maybe that’s one of the reasons why sports are so beloved here: It’s a forum where Little Brotheritis is actually productive. So many iconic American athletes—from Michael Jordan and Michael Phelps to Simone Biles—are younger siblings, learning from, competing with and eventually surpassing their older brothers and sisters.

Sometimes, being the underdog can be powerful. At the very least it makes the game more exciting. For my part, I’ve learned that Philadelphia, like a cheesesteak wit, can be an acquired taste. But I’m happy to be here, to bring my son up on a block where my mortgage is cheap, the magnolia trees bloom bright pink and the neighbors and I can chat about how big he’s grown. And when the day comes that someone out on the playground pokes fun at him, I hope I can teach him not to care.

Originally published in our 2020 field guide to Philadelphia.

Field Guide

Philadelphia

Historic monuments and red gravy joints, woodworkers and community organizers, local oddities and sports heartbreaks.

About the author

Sara Nović is the author of Girl at War, America Is Immigrants and her latest novel, True Biz. She has an MFA in fiction and literary translation from Columbia University and lives in South Philly.

Sara Nović is the author of Girl at War, America Is Immigrants and her latest novel, True Biz. She has an MFA in fiction and literary translation from Columbia University and lives in South Philly.

Read more like this

The Sounds of Houston

Turtlebox Audio carries the grit, soul, and sound of one of America's loudest music towns.